“We might be drawn inside a psychic bottleneck that holds that swallowing is just another name for incorporation or come to terms with our own indigestible thoughts. We might want to consider the consequence of our imaginations, like our mouths, being open to preemptive intrusion from the day we are born” (Capello, 2011).

Litofagos is a project series about the ingestion of stones and their biological inscription in the human body. With the infiltration of exogenous bodies we ingest their information, transcribing and transforming the objects and the way in which they are worshipped. The project develops through a series of collective actions, installations, video essays and publications. Litofagos reflects on different processes of ingestion, as well as on the biological, cultural and historical transformations that affect the objects consumed and those who consume them. It conceives the mouth as a mediating device between exterior and interior – a site of nurture, breath, aggression, appetite, language and even knowledge. The act of ingesting redraws the borders between subject and thing, biological and non-biological matter, and bonds of the communal body, re-signifying the collective construction of relationships between bodies.

Litofagos is in a process of continuous digestive transformation. To date the series consists of: endolito (Spain and United Kingdom), aerolito (Barcelona, Spain), megalito (Banff, Canada), daguerrolito (Zagreb, Croatia), bucarolito (Miami, US).

phagia graphia // The ingestion exogenous bodies

impregnates the bodies with foreign information and inscribes

in them new transferred forms.

{ Context of the project }

Everything begins with the mouth, one of the parts of our bodies where there is the most taking place, our most visible and vulnerable of orifices, the seat of so much that is essential to our staying alive. We recognise the mouth as a site of nurture, breath, aggression, appetite, language and even knowledge. Through our mouths we originally come to know the world and differentiate ourselves from it. This aperture is the membrane that separates our digestive anatomy from the outside world, and is one of the earliest doors that allow the intrusion of exogenous bodies to be absorbed into our organism. Like many animals, we still recognise the world through our mouth.

The mouth has always been a motive of control: how it can or cannot be used, what you can or cannot do with it, and moreover, what you can and cannot ingest.

In the 16th century, modern science named the abnormality of appetite ‘pica’.1 It is considered a psychological disorder characterised by an appetite for substances that are largely non-nutritive. Even today, it is an enigma for medicine in many aspects. Some dictionaries define it as: “Perversion of the appetite that appeals to inedible substances”. It was in the 17th century that medical science considered it essential to differentiate hunger from appetite: the first corresponded to the amount of food; the second, to the qualitative preference or selection of food. Pica was first described by the Greek physician and philosopher Hippocrates,2 but it was not addressed in medical texts until 1563.3 It was then that modern science stipulated the rules relating to appetite, in many cases applied and addressed in colonised territories.4 Various texts state that the abnormality of appetite was ruthlessly persecuted by considering it “demonic”. The stigmatisation of these practices obscured the record and documentation of the cultural and communal relations those ingestions generated.

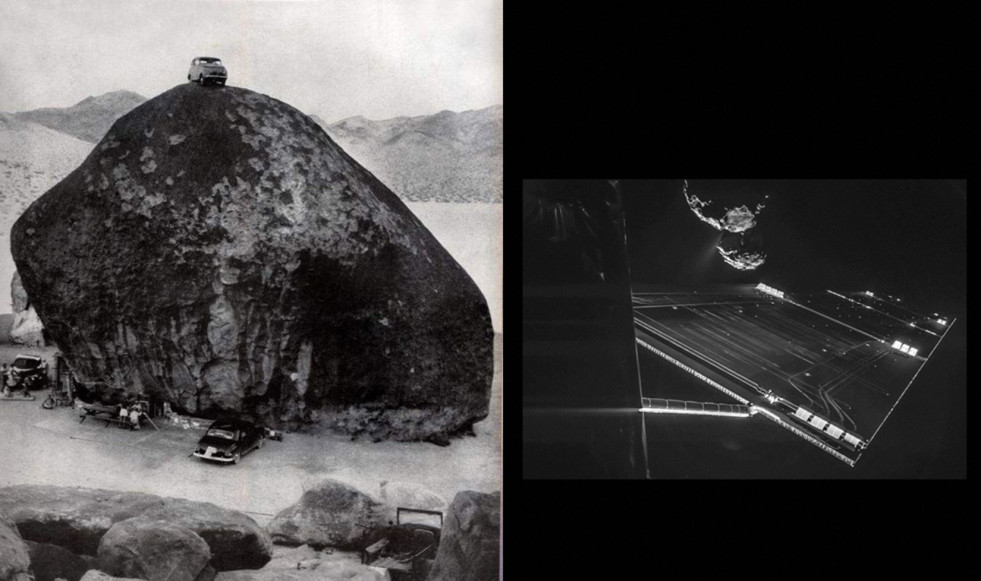

In the 1800s, geophagia was recorded in the southern United States as a common practice among the slave population, similar to the traditions of eating limestone (called odowa) in Kenya, white clay (called ayilo, agatawe or shile) in Ghana, or the ingestion of meteorites in southern-central Mali. Furthermore, the chroniclers mention the stories of travellers that traversed Peru during the colonial period and the first years of the Peruvian republic, leaving testimony of the existence of various forms of geophagia and how those customs were repressed. They highlight the fact that in the Amazon rainforest it is not easy to obtain salt, since it is located in very remote mines. The travellers recount their personal experience in Madre de Dios, where they observed how native jungle groups performed an annual pilgrimage in search of salty earth, known as collpas. Since antiquity, including in Greco-Roman culture, humanity has practiced geophagia. In those times, the reasons for this practice were medical, magical or religious. In America, and especially in Peru, allotriophagy was manifested since pre-Columbian times, as well as geophagia and the consumption of limestone powder, called llipt’a or llukta, ingested in conjunction with coca leaves.

The above are all stories of the concealed, syncretised actions that remain invisible to the writings of history. These actions were stigmatised, forbidden and consequently hidden and protected by those who practiced them. Perhaps we should consider another possible interpretation for those ingestions, far from being related to nutritional necessity, as modern medicine explained, but as a kind of affinity, an ancestrally learned or inherited manner of relating to the earth.

The time of stone is non-human; the time of stone is the time of Earth, the time of matter. Our understanding of it is just a fraction of a second in its existence. If we speak to stones they do not answer, but maybe they will do in fifty thousand years. Each stone is a condensation of time; it is a lucid surface for understanding the past. However, stones are not a passive relic of the past, but a yielding surface for inscription. Stones have their own time and space; lithic materiality pushes history into expansion, too large to be contained by periodisation. When people ingested them, perhaps they aimed to imprint themselves on those rocks and leave a record of themselves behind.

Each stone swallowed is a scientific gem that can provide unique geo-astro-biological information about our evolution. Here, stone is not only the photosensitive support as an inscribing apparatus. With the infiltration of exogenous bodies, we ingest their information, as they inscribe ours, transcribing and transforming materiality. There temporarily exists a symbiotic relation between the foreign object and the body, each briefly absorbing and communicating with the other.

To swallow is a voluntary action that takes food, drinks or other substances into the stomach to be absorbed or assimilated by drawing them through the throat and oesophagus. It implies trust in the person who offers you those substances to accept them without question or suspicion. In some cases it also involves believing in the digestion and absorption of those substances.

An object once ingested is part body, enjoyed and intimate, and navigates with itinerant strangeness through its host. An inherent intimacy, adhered and later expelled—but not forgotten or easily disposed of.

1 According to modern medicine: “The specific type of pica is determined by the kind of food or substance ingested, the most common appellations being: geophagia or eating earth, pagophagia or eating ice, and amylophagia or eating purified starch. Depending on the psychological-psychiatric condition of the individual, the severity of the case varies according to the strangeness of appetite; thus, in pregnant women with iron-deficiency anaemia, geophagia or pagophagia are frequent.”

2 Hippocrates of Kos compiled in his texts between 460-377 BC different cases of geophagia that mark the transition from a magical view of health and disease to one of belief in causation. For centuries, Hippocrates’ textbook was a cornerstone of medical practice, so we can assume that Greek and Roman physicians were familiar with geophagia.

3 The first person to use the word ‘pica’ to refer to this supposed syndrome was the French surgeon Frances Ambroise Pareé in the mid-sixteenth century. He took the word from the Latin name for the Eurasian magpie (Pica pica), possibly by analogy with the behaviour of this bird, that is known to ingest practically anything out of hunger or curiosity.

4 It seems significant to highlight the different attitudes that existed between the Inca and Spanish conquerors. The first allowed the practice of local customs, as long as obedience to Inca authority was maintained; the second ruthlessly persecuted everything he did not understand and branded it “demonic”. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the second did not managed to eliminate the practice of geophagy, but made it more drastic.